My Friend Ruth

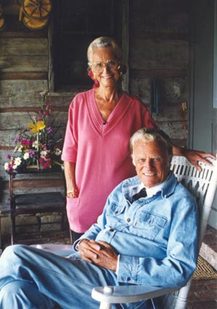

My friend Ruth -- from 1943 until her death in June this year, the wife of Billy Graham -- was the first person ever to talk to me about heaven. As I put the book that eventually followed, All the Way to Heaven online this month, I keep thinking back to that conversation so many years ago.

Ruth and I were sitting at the big round table in the eat-in kitchen of the Grahams' rustic home in Little Piney Cove, North Carolina, working on a book for children and discussing what understanding of spiritual matters a six-year-old might have.

"Heaven for instance," Ruth said. "What did that word mean to you when you were that age?"

I looked at her, puzzled. "I don't think it meant anything. I don't think I even knew it."

"But… when your minister talked about it, you must had some idea!"

I didn't have a minister, I told her; my family didn't go to church. It was Ruth's turn to stare. The daughter of missionaries, churchgoing had been the anchor of her young life. An invisible, ever-near other world was as real to her at age six, she said, as the furniture in her bedroom.

Ruth grew up in the rural China of the old warlord days, where the Christian community lived in a high-walled compound. Outside that compound was a world of very visible evil -- rich landlords and starving peasants, bribe-taking judges, legal torture, little girls sold into slavery. Within its walls, by contrast, were kindness, love, dignity.

"They were microcosms of heaven and hell," Ruth said. "I had no trouble, at six, picturing either realm. Nor understanding that it was Jesus who made the difference."

The world I grew up in, on the other hand, I told her, revealed no such distinction between godly and ungodly. All the citizens of Scarsdale, New York, to a child's eyes anyway, were equally law-abiding. If some of them went to church, they seemed no different from the rest. "Heaven", when eventually I encountered the word, I pictured much as I did the Land of Oz, an imaginary place somewhere over the rainbow.

Ruth, though, knew from earliest childhood not only that heaven was real, but that it was a far happier world than this one. "My parents often talked to me about it. There'll be no suffering there, they said. No sorrow, no separation!"

When her own children came along, Ruth made sure they too learned early about this wondrous realm. I remember being at the Grahams' home once when a beloved dog died. When they got to heaven, the children asked their mother anxiously, would the dog be there? Instead of smiling at the naïve notion, Ruth went, as she always did when confronted with a question for the first time, to the Bible. Heaven, she concluded from her Scripture search, is where each of us will be totally happy. And if someone's happiness depends on finding a particular animal there, then yes, heaven might well house dogs -- horses, cats, canaries.

All of our life here on earth, Ruth believed, was a journey to our real, eternal home. Believing this didn't mean that her journey was an easy one; we get to know Jesus best, she often said, when the road is rough. In The Glory of Ruth (Guideposts, October, 2007) I write about one such rough road: Ruth's responsibility for raising five children virtually alone, with a husband away nine weeks out of ten.

Nor did it mean that she herself had no growing to do along the way. As a young woman, she told me, she believed it was her solemn duty to present the way of salvation to every single person she encountered. If she should fail to do this, and the person died in his ignorance, she would have to answer personally for his eternal damnation. "When I'd buy a train ticket, for instance, I'd always hand the ticket seller a tract along with the money. There's one person, I'd think, that I don't have to worry about. I had a lot of maturing to do before I understood what sharing Jesus means!"

But though Ruth's understanding of evangelism deepened, her certainty of its importance never changed. Jesus, experience taught her, has many ways of reaching out to people. "But he himself is the one way to heaven. It was his death that won our salvation, his resurrection that gives eternal life. There's just no other path that will take us there."

Ruth's insistence on the all-importance of the atonement was so great that for a children's Christmas book we wrote together, she insisted that the cover illustration include a cross along with the familiar manger scene. The artist was resistant, the publisher aghast. A cross? An instrument of torture and death on a book for the season of joy?

"But where is the joy," Ruth asked, "without the death that frees us from sin? Without Good Friday and Easter, Christmas is meaningless."

The book, Our Christmas Story, begins not with the Gospel of Luke, but with the Book of Genesis, tracing the whole tragedy of man's separation from God that Jesus, in his birth, came to heal. The cross did appear on the cover, and children, always more realistic than adults, had no trouble at all accepting evil and good in the same story.

People who look for another way to heaven than through Jesus' sacrifice, Ruth told me, reminded her of a dear woman who for many years had helped out with the cooking and the cleaning and the endless laundry in the lively Graham household. When Ruth and the children were given a rare opportunity to join Bill on a crusade in Europe, Ruth wanted to share the experience with this faithful helper.

The woman was clearly thrilled to be invited. Again and again she thanked Ruth for including her, told her how excited she was at the prospect, how much she'd always wanted to see the wonders of Europe. There was one drawback, she confessed. "She was unwilling to fly and she was afraid to go by boat. Other than that, she said, of course she'd go with us."

Jesus, the Way -- "the one way" -- to heaven. The Way Ruth walked for 87 years. How often, since June, I've thought of my friend "totally happy" in the world I first glimpsed through her eyes of faith.

Ruth and I were sitting at the big round table in the eat-in kitchen of the Grahams' rustic home in Little Piney Cove, North Carolina, working on a book for children and discussing what understanding of spiritual matters a six-year-old might have.

"Heaven for instance," Ruth said. "What did that word mean to you when you were that age?"

I looked at her, puzzled. "I don't think it meant anything. I don't think I even knew it."

"But… when your minister talked about it, you must had some idea!"

I didn't have a minister, I told her; my family didn't go to church. It was Ruth's turn to stare. The daughter of missionaries, churchgoing had been the anchor of her young life. An invisible, ever-near other world was as real to her at age six, she said, as the furniture in her bedroom.

Ruth grew up in the rural China of the old warlord days, where the Christian community lived in a high-walled compound. Outside that compound was a world of very visible evil -- rich landlords and starving peasants, bribe-taking judges, legal torture, little girls sold into slavery. Within its walls, by contrast, were kindness, love, dignity.

"They were microcosms of heaven and hell," Ruth said. "I had no trouble, at six, picturing either realm. Nor understanding that it was Jesus who made the difference."

The world I grew up in, on the other hand, I told her, revealed no such distinction between godly and ungodly. All the citizens of Scarsdale, New York, to a child's eyes anyway, were equally law-abiding. If some of them went to church, they seemed no different from the rest. "Heaven", when eventually I encountered the word, I pictured much as I did the Land of Oz, an imaginary place somewhere over the rainbow.

Ruth, though, knew from earliest childhood not only that heaven was real, but that it was a far happier world than this one. "My parents often talked to me about it. There'll be no suffering there, they said. No sorrow, no separation!"

When her own children came along, Ruth made sure they too learned early about this wondrous realm. I remember being at the Grahams' home once when a beloved dog died. When they got to heaven, the children asked their mother anxiously, would the dog be there? Instead of smiling at the naïve notion, Ruth went, as she always did when confronted with a question for the first time, to the Bible. Heaven, she concluded from her Scripture search, is where each of us will be totally happy. And if someone's happiness depends on finding a particular animal there, then yes, heaven might well house dogs -- horses, cats, canaries.

All of our life here on earth, Ruth believed, was a journey to our real, eternal home. Believing this didn't mean that her journey was an easy one; we get to know Jesus best, she often said, when the road is rough. In The Glory of Ruth (Guideposts, October, 2007) I write about one such rough road: Ruth's responsibility for raising five children virtually alone, with a husband away nine weeks out of ten.

Nor did it mean that she herself had no growing to do along the way. As a young woman, she told me, she believed it was her solemn duty to present the way of salvation to every single person she encountered. If she should fail to do this, and the person died in his ignorance, she would have to answer personally for his eternal damnation. "When I'd buy a train ticket, for instance, I'd always hand the ticket seller a tract along with the money. There's one person, I'd think, that I don't have to worry about. I had a lot of maturing to do before I understood what sharing Jesus means!"

But though Ruth's understanding of evangelism deepened, her certainty of its importance never changed. Jesus, experience taught her, has many ways of reaching out to people. "But he himself is the one way to heaven. It was his death that won our salvation, his resurrection that gives eternal life. There's just no other path that will take us there."

Ruth's insistence on the all-importance of the atonement was so great that for a children's Christmas book we wrote together, she insisted that the cover illustration include a cross along with the familiar manger scene. The artist was resistant, the publisher aghast. A cross? An instrument of torture and death on a book for the season of joy?

"But where is the joy," Ruth asked, "without the death that frees us from sin? Without Good Friday and Easter, Christmas is meaningless."

The book, Our Christmas Story, begins not with the Gospel of Luke, but with the Book of Genesis, tracing the whole tragedy of man's separation from God that Jesus, in his birth, came to heal. The cross did appear on the cover, and children, always more realistic than adults, had no trouble at all accepting evil and good in the same story.

People who look for another way to heaven than through Jesus' sacrifice, Ruth told me, reminded her of a dear woman who for many years had helped out with the cooking and the cleaning and the endless laundry in the lively Graham household. When Ruth and the children were given a rare opportunity to join Bill on a crusade in Europe, Ruth wanted to share the experience with this faithful helper.

The woman was clearly thrilled to be invited. Again and again she thanked Ruth for including her, told her how excited she was at the prospect, how much she'd always wanted to see the wonders of Europe. There was one drawback, she confessed. "She was unwilling to fly and she was afraid to go by boat. Other than that, she said, of course she'd go with us."

Jesus, the Way -- "the one way" -- to heaven. The Way Ruth walked for 87 years. How often, since June, I've thought of my friend "totally happy" in the world I first glimpsed through her eyes of faith.