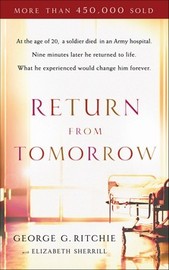

Return from Tomorrow

"It was a phone call from Catherine Marshall," writes Elizabeth, "that made me eager to meet George Ritchie. I recognized the name. I'd been hearing about him for several years, ever since receiving a letter from a reader of Guideposts magazine recounting the "incredible" story he'd just heard. A certain Dr. George Ritchie had spoken at his church that morning and kept everyone spellbound with an account of his own clinical death, his resuscitation nine minutes later, and what he experienced in between. Someone from the magazine should come to Richmond, Virginia, the letter concluded, and write the story.

"Incredible" is the right word, I'd thought as I added the letter to my already bulging Story Leads folder. I didn't doubt that the letter writer had heard an inspiring speaker, but... dying and coming back to report on the next world? Pretty far fetched.

I did mention the letter to my husband John and other editors at Guideposts, and all of us had the same reaction. Too far out!

Over the next two years the magazine received several more letters about this same George Ritchie. "I'd gone to church all my life," a 79-year-old woman wrote, "but after hearing Dr. Ritchie I went home and committed my life to Jesus for the very first time."

That was a recurrent theme in these letters: a casual churchgoer getting serious about his faith. Scare tactics, was my guess. The fellow was probably frightening people with some outlandish tale about the fate of non-believers in the afterlife.

Then came that phone call from Catherine. Though at that time we knew each other only through the mail and over the phone, I knew by working on her manuscripts that she was a bulldog for facts with little use for spiritual flights of fantasy.

Her voice over the phone bubbled with excitement. "I've just met the most remarkable man! His name is George Ritchie..."

They'd had a long conversation from which she'd come away absolutely convinced of his truthfulness. "Tib, this story belongs in Guideposts! You've simply got to interview him and do an article!"

Catherine was the last person on earth, I was sure, to be bamboozled by a sensation seeker. If she felt that this Dr. Ritchie had something important to say, I was ready to listen. At the magazine, though, the idea was again turned down. It would mean endorsing a tale no one could prove. Someday, maybe, as part of a series presenting many different accounts of deathbed visions.

In the early sixties that "someday" arrived. By then the whole subject of threshold experiences -- people who, near death, believed they'd had a glimpse of another world -- was very much in the air. In April, 1963, Guideposts began a ten-part series titled "Life after Death." For the third installment I traveled down to Richmond, Virginia, to interview George Ritchie.

Because of the impact he had on people, I was expecting to meet a human dynamo, fluent, energetic and persuasive. Instead, I found myself in the presence of a tall, gentle, soft-spoken, rather reserved man of thirty-nine with a head of luxuriant dark hair and the kindest brown eyes I'd ever seen.

We were meeting in Dr. Ritchie's consulting room at Memorial Hospital in Richmond, at the close of his workday. Though clearly tired after the long hours with patients, he was courtesy itself, holding my chair, inquiring about my comfort on the flight down, very much the southern gentleman. In the drawl unique to that part of Virginia, he began to relate his story.

It began in December, 1943, when a 20-year-old buck private in basic training at Camp Barkeley, Texas, began to run a fever...

At 7:00 we broke off the interview and drove to his home, a substantial red brick, Colonial Williamsburg style house, just a mile away. There I met his wife Marguerite, with blue eyes and light brown hair a striking physical contrast to her husband. At dinner we were joined by their two young children, Bonnie Louise and John, after which the three adults -- we were now George, Marguerite and Tib to each other -- continued the interview.

Did I believe the extraordinary story George was relating? It was clear, at any rate, that he himself believed it. And after only a few hours' acquaintance, I recognized in him a scientifically oriented man, not given to imagination.

It was Marguerite's comments, though, that told me most. George's entire life since his return from clinical death, she said, had been directed by what he had seen in those nine minutes of another kind of existence. It was from her that I learned about his work with young people, the Universal Youth Corps he'd founded (which became the inspiration for the Peace Corps), his medical service without pay for those who could not afford it, his many charities, his entire life of loving and giving. Could delirium brought on by fever or drugs, I asked myself, have dominated a man's every act and decision for 20 years?

I spent the night there and next morning George and I resumed our talks. "Do you believe you've had an authentic preview of what awaits us after death?" I asked him.

No, he said. "I have no idea what the next life will be like." He'd been permitted to go, he reminded me, only as far as the doorway. As for the things he'd seen from there, he didn't know whether he'd see them after his actual demise, or not. What he was sure of was that he'd been in the presence of Christ, and that this remained the most important event of his life.

I flew home the following day with 27 pages of notes in my briefcase. Often after an interview there's a particular scene I can't wait to write. In this case it was George, a young soldier in the hospital at Camp Barkeley, walking down a corridor with another man bearing down on him from the opposite direction. He's coming too close, they're going to collide! "Look out!' George shouts. The next second the man has passed him, walking through the very space where George is standing...

George's story appeared in the June issue of Guideposts, and by July I'd received at least a dozen letters from people recounting their own near-death experiences. Every article in the series brought similar batches of mail; it proved to be the most popular one the magazine had ever run, with George's story readers' favorite.

After the series ended in January, 1964, I read through all the letters it attracted, nearly 70 of them, describing a threshold event, either the writer's own or someone else's. The more I read, the more I realized both how similar and how different George's account was.

Light, so central to George's story, was a common report, though unlike his, the light usually appeared far off at the end of a tunnel. A beautiful landscape was often recalled, and departed loved ones coming to welcome the new arrival -- both absent in George's experience. Present in his, though, and missing from most others', were two elements: a vision of hell as well as heaven, and the absolute centrality of Christ. Instead of Return from Tomorrow, the title of this book might well be "An Encounter with Jesus".

What was common to almost every account, however, was a sense of joy and peace unlike any experienced on earth. Like George, most reported a tremendous sorrow at having to return to a life so inferior to the one they'd glimpsed. When, many years later, I wrote All the Way to Heaven about my own intimations of another world, I referred to this near-universal testimony: the afterlife is infinitely preferable to this one.

Over the years, George and I kept in touch through the mail. Shortly after my trip to Richmond, he moved his family to Charlottesville, giving up his thriving medical practice and the presidency of the Richmond Academy of General Practice, to study psychiatry at the University of Virginia. "I got tired of treating diseases rather than people," he wrote to me. At the hospital they had to speed patients through; fifteen, twenty minutes was all he'd have with someone. Psychiatry, he thought, would offer at least a chance of real healing.

In 1973 it was ten years after the Guideposts article appeared -- as long as I usually hold onto files on a story. I discarded my other 1963 records, but when it came to George's... There were so many details of his experience I hadn't been able to fit within the magazine's 1800-word limit!

I put his file back in the cabinet.

But though I hadn't been able to get all the highpoints of George's story into the magazine piece, I'd often talked about them. And of course in was Catherine who wouldn't let the matter end there. "You must tell it all! God wants the whole story out there! You should do a book."

So eventually I wrote George asking what he thought. In September, 1977, time opened up for both of us and so I flew, not to Richmond this time, but to Charlottesville where George had remained after finishing his residency in psychiatry at the University of Virginia Hospital. He and Marguerite (their children were now pursuing their own careers) had bought an airy one-story home with a large living room and a big front porch on Carter's Creek.

There the three of us picked up the conversations begun fourteen years earlier. The book appeared in 1978 and has never since then been out of print. As this 30th anniversary edition goes to press, George has retired from his psychiatry practice and he and Marguerite have moved to the Westminster Canterbury retirement complex in Irvington, Virginia. "Retired from professional work," George says, "but never from the chief business of mine and every life -- learning to love in this world to prepare us well for the next."

Buy Return From Tomorrow from Amazon.com

"Incredible" is the right word, I'd thought as I added the letter to my already bulging Story Leads folder. I didn't doubt that the letter writer had heard an inspiring speaker, but... dying and coming back to report on the next world? Pretty far fetched.

I did mention the letter to my husband John and other editors at Guideposts, and all of us had the same reaction. Too far out!

Over the next two years the magazine received several more letters about this same George Ritchie. "I'd gone to church all my life," a 79-year-old woman wrote, "but after hearing Dr. Ritchie I went home and committed my life to Jesus for the very first time."

That was a recurrent theme in these letters: a casual churchgoer getting serious about his faith. Scare tactics, was my guess. The fellow was probably frightening people with some outlandish tale about the fate of non-believers in the afterlife.

Then came that phone call from Catherine. Though at that time we knew each other only through the mail and over the phone, I knew by working on her manuscripts that she was a bulldog for facts with little use for spiritual flights of fantasy.

Her voice over the phone bubbled with excitement. "I've just met the most remarkable man! His name is George Ritchie..."

They'd had a long conversation from which she'd come away absolutely convinced of his truthfulness. "Tib, this story belongs in Guideposts! You've simply got to interview him and do an article!"

Catherine was the last person on earth, I was sure, to be bamboozled by a sensation seeker. If she felt that this Dr. Ritchie had something important to say, I was ready to listen. At the magazine, though, the idea was again turned down. It would mean endorsing a tale no one could prove. Someday, maybe, as part of a series presenting many different accounts of deathbed visions.

In the early sixties that "someday" arrived. By then the whole subject of threshold experiences -- people who, near death, believed they'd had a glimpse of another world -- was very much in the air. In April, 1963, Guideposts began a ten-part series titled "Life after Death." For the third installment I traveled down to Richmond, Virginia, to interview George Ritchie.

Because of the impact he had on people, I was expecting to meet a human dynamo, fluent, energetic and persuasive. Instead, I found myself in the presence of a tall, gentle, soft-spoken, rather reserved man of thirty-nine with a head of luxuriant dark hair and the kindest brown eyes I'd ever seen.

We were meeting in Dr. Ritchie's consulting room at Memorial Hospital in Richmond, at the close of his workday. Though clearly tired after the long hours with patients, he was courtesy itself, holding my chair, inquiring about my comfort on the flight down, very much the southern gentleman. In the drawl unique to that part of Virginia, he began to relate his story.

It began in December, 1943, when a 20-year-old buck private in basic training at Camp Barkeley, Texas, began to run a fever...

At 7:00 we broke off the interview and drove to his home, a substantial red brick, Colonial Williamsburg style house, just a mile away. There I met his wife Marguerite, with blue eyes and light brown hair a striking physical contrast to her husband. At dinner we were joined by their two young children, Bonnie Louise and John, after which the three adults -- we were now George, Marguerite and Tib to each other -- continued the interview.

Did I believe the extraordinary story George was relating? It was clear, at any rate, that he himself believed it. And after only a few hours' acquaintance, I recognized in him a scientifically oriented man, not given to imagination.

It was Marguerite's comments, though, that told me most. George's entire life since his return from clinical death, she said, had been directed by what he had seen in those nine minutes of another kind of existence. It was from her that I learned about his work with young people, the Universal Youth Corps he'd founded (which became the inspiration for the Peace Corps), his medical service without pay for those who could not afford it, his many charities, his entire life of loving and giving. Could delirium brought on by fever or drugs, I asked myself, have dominated a man's every act and decision for 20 years?

I spent the night there and next morning George and I resumed our talks. "Do you believe you've had an authentic preview of what awaits us after death?" I asked him.

No, he said. "I have no idea what the next life will be like." He'd been permitted to go, he reminded me, only as far as the doorway. As for the things he'd seen from there, he didn't know whether he'd see them after his actual demise, or not. What he was sure of was that he'd been in the presence of Christ, and that this remained the most important event of his life.

I flew home the following day with 27 pages of notes in my briefcase. Often after an interview there's a particular scene I can't wait to write. In this case it was George, a young soldier in the hospital at Camp Barkeley, walking down a corridor with another man bearing down on him from the opposite direction. He's coming too close, they're going to collide! "Look out!' George shouts. The next second the man has passed him, walking through the very space where George is standing...

George's story appeared in the June issue of Guideposts, and by July I'd received at least a dozen letters from people recounting their own near-death experiences. Every article in the series brought similar batches of mail; it proved to be the most popular one the magazine had ever run, with George's story readers' favorite.

After the series ended in January, 1964, I read through all the letters it attracted, nearly 70 of them, describing a threshold event, either the writer's own or someone else's. The more I read, the more I realized both how similar and how different George's account was.

Light, so central to George's story, was a common report, though unlike his, the light usually appeared far off at the end of a tunnel. A beautiful landscape was often recalled, and departed loved ones coming to welcome the new arrival -- both absent in George's experience. Present in his, though, and missing from most others', were two elements: a vision of hell as well as heaven, and the absolute centrality of Christ. Instead of Return from Tomorrow, the title of this book might well be "An Encounter with Jesus".

What was common to almost every account, however, was a sense of joy and peace unlike any experienced on earth. Like George, most reported a tremendous sorrow at having to return to a life so inferior to the one they'd glimpsed. When, many years later, I wrote All the Way to Heaven about my own intimations of another world, I referred to this near-universal testimony: the afterlife is infinitely preferable to this one.

Over the years, George and I kept in touch through the mail. Shortly after my trip to Richmond, he moved his family to Charlottesville, giving up his thriving medical practice and the presidency of the Richmond Academy of General Practice, to study psychiatry at the University of Virginia. "I got tired of treating diseases rather than people," he wrote to me. At the hospital they had to speed patients through; fifteen, twenty minutes was all he'd have with someone. Psychiatry, he thought, would offer at least a chance of real healing.

In 1973 it was ten years after the Guideposts article appeared -- as long as I usually hold onto files on a story. I discarded my other 1963 records, but when it came to George's... There were so many details of his experience I hadn't been able to fit within the magazine's 1800-word limit!

I put his file back in the cabinet.

But though I hadn't been able to get all the highpoints of George's story into the magazine piece, I'd often talked about them. And of course in was Catherine who wouldn't let the matter end there. "You must tell it all! God wants the whole story out there! You should do a book."

So eventually I wrote George asking what he thought. In September, 1977, time opened up for both of us and so I flew, not to Richmond this time, but to Charlottesville where George had remained after finishing his residency in psychiatry at the University of Virginia Hospital. He and Marguerite (their children were now pursuing their own careers) had bought an airy one-story home with a large living room and a big front porch on Carter's Creek.

There the three of us picked up the conversations begun fourteen years earlier. The book appeared in 1978 and has never since then been out of print. As this 30th anniversary edition goes to press, George has retired from his psychiatry practice and he and Marguerite have moved to the Westminster Canterbury retirement complex in Irvington, Virginia. "Retired from professional work," George says, "but never from the chief business of mine and every life -- learning to love in this world to prepare us well for the next."

Buy Return From Tomorrow from Amazon.com